The Metropolitan Museum of Art has been accused of “secretly” selling Van Gogh masterpieces looted from Jews fleeing the Nazis – and trying to arrange a shelter designed to last 100 years.

The museum is being sued by the Jewish family who owned “The Olive Picking” before World War II and want it back. It could be worth $70 million.

The painting was bought by the Met in 1956 from Brooke Astor – the socialite who died aged 105 in 2007 – then sold secretly in 1972 and disappeared from public view.

It only appeared in 2019 in the catalog of a newly opened gallery in Athens, Greece.

The breakthrough allowed the family of Jewish collector Hedwig Stern, who died in 1987, to piece together what they now claim happened.

Now nine of Stern’s heirs are suing both the Met and the Greek museum’s operator, the Basil and Elise Goulandris Foundation, in federal court in Northern California to return it, saying they are the victims of decades of cover-ups and lies.

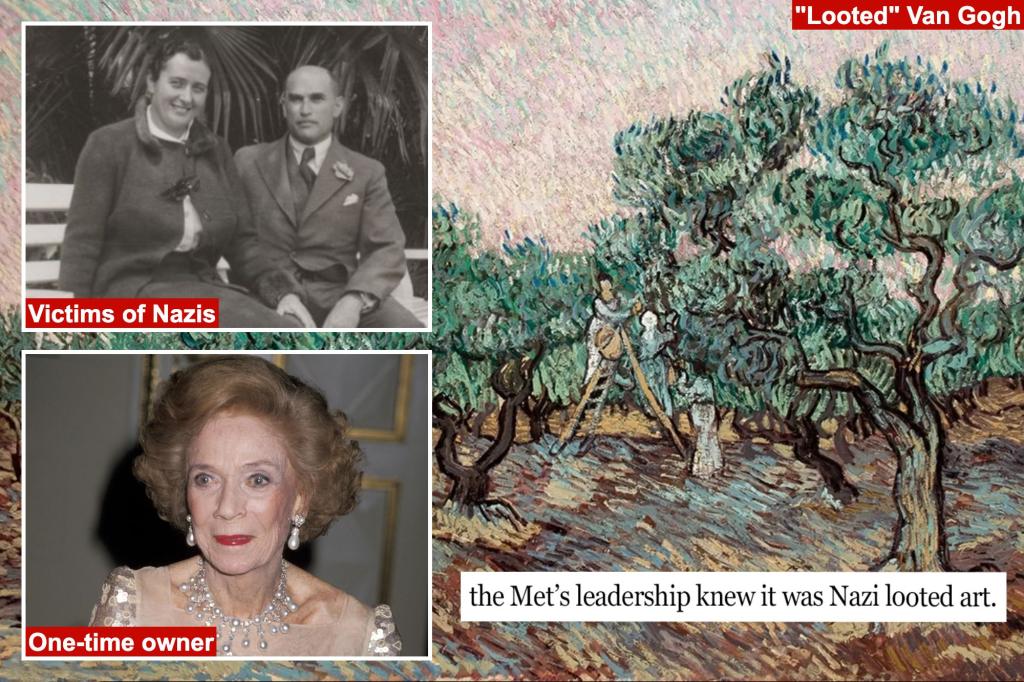

Hedwig Stern (left) and her husband, Fritz (right), bought a Van Gogh in 1935, the year this photo was taken while they were on vacation in Locarno, Switzerland.

Hedwig Stern (left) and her husband, Fritz (right), bought a Van Gogh in 1935, the year this photo was taken while they were on vacation in Locarno, Switzerland.

The Met is fighting the case, saying it did not know the work was stolen. The nine plaintiffs include Stern’s grandchildren and step-grandchildren, who now live in Oakland and Los Angeles, Calif., Washington state and Israel. Their lawyers declined to comment.

The case threatens to open the Met’s secret files on one of its most famous curators, former “Monuments Man” Theodore Rousseau, who bought and sold Van Goghs.

Vincent Van Gogh’s “The Olive Picking” was in the Met’s collection until 1972 when it was quietly disposed of. Now the family of a Jewish woman who was forced to abandon her when she fled Nazi Germany is suing, saying the Met covered up her dealings in the art of robbery.

Vincent Van Gogh’s “The Olive Picking” was in the Met’s collection until 1972 when it was quietly disposed of. Now the family of a Jewish woman who was forced to abandon her when she fled Nazi Germany is suing, saying the Met covered up her dealings in the art of robbery.

Stern and his family had a rich life in Munich, exhibiting art in their home. But they had to flee from Nazi persecution, and could not bring their art, including Van Gogh and Renoir.

Stern and his family had a rich life in Munich, exhibiting art in their home. But they had to flee from Nazi persecution, and could not bring their art, including Van Gogh and Renoir.

Van Gogh, seen in self-portrait, painted “The Olive Picking” a few months before his death. It is one of 15 series inspired by the annual harvest in Provence. De Agostini via Getty Images

Van Gogh, seen in self-portrait, painted “The Olive Picking” a few months before his death. It is one of 15 series inspired by the annual harvest in Provence. De Agostini via Getty Images

Socialite Brooke Astor and her husband, Vincent, whose portrait is pictured in front of her, once owned a Van Gogh. Vincent Astor bought it in New York after World War II. AP

Socialite Brooke Astor and her husband, Vincent, whose portrait is pictured in front of her, once owned a Van Gogh. Vincent Astor bought it in New York after World War II. AP

“The Olive Picking,” painted by the Dutch artist in 1889 shortly before his death, was purchased in 1935 by Stern, an heiress and doctor’s wife, from Munich’s Heinrich Thannhauser Gallery, adding to his Impressionist collection.

But when she, her husband and their six children tried to escape the rising tide of Nazi repression in 1936, the Gestapo prevented them from taking “The Olive Picking.”

He instructed his lawyer to sell it and a Renoir through the same gallery. The Nazis kept only 55,000 Reichsmarks; Stern and his family found safety in Berkeley, Calif.

Theodore Rousseau was part of the Monuments Men, a unit set up to restore Nazi-looted art, before becoming one of the Met’s most influential curators. The Sterns claim he definitely knows the history of Van Gogh.the basic monument of men and women

Theodore Rousseau was part of the Monuments Men, a unit set up to restore Nazi-looted art, before becoming one of the Met’s most influential curators. The Sterns claim he definitely knows the history of Van Gogh.the basic monument of men and women

Stern was a victim of Hitler’s persecution, forced to flee for her life with her husband and their six children. They found protection in America, but their descendants say they were let down by New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Bettmann Archives

Stern was a victim of Hitler’s persecution, forced to flee for her life with her husband and their six children. They found protection in America, but their descendants say they were let down by New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Bettmann Archives

In 1948, Thannhauser’s son, Justin, brought the painting to New York and sold it to Vincent Astor, whose financier father, John Jacob Astor IV, had died on the Titanic, and who in 1953 married socialite Brooke Russell.

In 1955, Brooke Astor asked the Manhattan gallery Knoedler & Co. to sell Van Gogh to the museum, according to court papers.

Rousseau, the Met’s curator, approved the $125,000 purchase — even though Knoedler was on the State Department’s “red flag” list of dealers in looted Jewish treasures.

“The Olive Picking” is also on a separate list of looted art because Stern tried to recover the painting after the war, going to Munich and Washington to meet with US officials “without success.”

Brooke Astor, seen in 1994, directed the sale of “The Olive Picking” in 1955. She later became a Met trustee, and died at age 105 in 2007. Ron Galella Collection via Getty Images

Brooke Astor, seen in 1994, directed the sale of “The Olive Picking” in 1955. She later became a Met trustee, and died at age 105 in 2007. Ron Galella Collection via Getty Images

The Met is fighting the Stern family’s lawsuit, saying it didn’t know about the Van Gogh being stolen when it bought it or when it sold it. But the museum has been revealed to have closed the archive of the curator who bought it until 2073. Helayne Seidman

The Met is fighting the Stern family’s lawsuit, saying it didn’t know about the Van Gogh being stolen when it bought it or when it sold it. But the museum has been revealed to have closed the archive of the curator who bought it until 2073. Helayne Seidman

And Rousseau must have known the truth about the painting, Stern’s descendants say, because he had been part of an elite unit known as the “Monuments Men,” which tracked down and restored Nazi-looted art as the Allied forces toppled Hitler’s regime.

A US Navy officer, he worked for the Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner of the CIA, investigating Nazi art thefts until 1946. “He was one of the world’s experts in the art of looting,” the Stern family said.

“Looted Nazi art was all over the art market at the time,” said Michael Gross, author of “Rogues’ Gallery: The Secret Story of the Lust, Lies, Greed and Betrayals that Made the Metropolitan Museum of Art.”

This is the passport Hedwig Stern used to get out of Germany in 1936, fleeing the persecution that ended with the Holocaust for safety in the US. But the Gestapo prevented him from boarding the Van Gogh, leading to his family’s current court battle.

This is the passport Hedwig Stern used to get out of Germany in 1936, fleeing the persecution that ended with the Holocaust for safety in the US. But the Gestapo prevented him from boarding the Van Gogh, leading to his family’s current court battle.

Hedwig and Fritz Stern and their children, including daughter Eva (left), build a new life in the US. But when this photo was taken in 1948, he had begun a quest to get his Van Gogh back — and was still trying when the Met bought it in 1955.

Hedwig and Fritz Stern and their children, including daughter Eva (left), build a new life in the US. But when this photo was taken in 1948, he had begun a quest to get his Van Gogh back — and was still trying when the Met bought it in 1955.

“The original surgery was not as sophisticated as it is now,” he told The Post.

Stern’s descendants claim Rousseau was working under State Department rules that would have informed the museum about the purchase.

Then in 1972, they say, Rousseau turned to the Marlborough Gallery to organize a hush-hush sale for an undisclosed sum, which the Met said was more than $75,000.

The sale was kept secret for months, then condemned as a “breach of the public trust” by the American Art Dealers Association, the New York Times reported at the time.

Rousseau, before becoming one of the Met’s most famous curators, was one of the “Monument Men,” the elite art hunters portrayed by George Clooney and Matt Damon in the 2014 film of the same name.Kobal/Shutterstock

Rousseau, before becoming one of the Met’s most famous curators, was one of the “Monument Men,” the elite art hunters portrayed by George Clooney and Matt Damon in the 2014 film of the same name.Kobal/Shutterstock

Basil Goulandris was the obvious buyer in 1972. He died in 1994 after a productive life spending his fortune as a Greek shipping tycoon to amass a large art collection. Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

Basil Goulandris was the obvious buyer in 1972. He died in 1994 after a productive life spending his fortune as a Greek shipping tycoon to amass a large art collection. Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

The Met said at the time that it was a “smaller work” that was being sold to help buy a $5.5 million Velazquez painting. But the Stern family says that’s a lie; the painting was purchased in 1971 with money from, among others, Brooke Astor.

A similar Van Gogh work — “Wooden Huts Among Olive Trees and Cypresses” — sold at auction in 2021 for more than $71 million.

Rousseau died in 1973 and the Met ordered the archives of his papers sealed until 2073, which the Stern family says will let the museum keep the truth about its Van Gogh secret for decades to come.

The painting’s ownership remains unclear, Stern’s descendants say, with the buyer in 1972 being Greek shipping heir Basil Goulandris and his wife, Elise. They raised $3 billion before their deaths.

Goulandris and his wife, Elise, who died in 2000, created a foundation that opened a museum in 2019 to showcase their collection. His catalog includes “The Olive Picking,” which the Stern family now wants returned to them. Goulandris Foundation

Goulandris and his wife, Elise, who died in 2000, created a foundation that opened a museum in 2019 to showcase their collection. His catalog includes “The Olive Picking,” which the Stern family now wants returned to them. Goulandris Foundation

The Goulandris Foundation Gallery in Athens, which opened in 2019, is where “The Olive Picking” is on display, although the foundation does not acknowledge that the work belongs to Basil and Elise Goulandris.Wikimedia Commons

The Goulandris Foundation Gallery in Athens, which opened in 2019, is where “The Olive Picking” is on display, although the foundation does not acknowledge that the work belongs to Basil and Elise Goulandris.Wikimedia Commons

The couple’s foundation listed “The Olive Picking” in the 2019 catalog for its new Athens museum, but did not say it belonged to the couple or disclose Stern’s ownership. The foundation declined to comment through a spokeswoman, citing the litigation on Wednesday.

The Met said in a statement that “during the Met’s ownership of the painting,” there was no record that it belonged to the Stern family, adding, “that information was not available until decades after the painting left the museum’s collection.”

Categories: Trending

Source: thtrangdai.edu.vn/en/